Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in the treatment of osteosarcoma (Review)

- Authors:

- Published online on: February 22, 2024 https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2024.5628

- Article Number: 40

-

Copyright: © Yu et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License.

Abstract

1. Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) is a frequently occurring primary bone tumor in children, adolescents and young adults with a worldwide incidence rate of 3.4 cases per 10,000 individuals per year (1,2). OS commonly occurs in the metaphysis of long bones, mostly in the humerus, distal femur and proximal tibia, and is characterized by swelling and persistent pain in the affected bone (3). Although the combination of radical surgery and systemic chemotherapy improves the prognosis of patients with primary OS, its side effects significantly affect patients' quality of life. Moreover, the prognosis of metastatic or recurrent OS remains unsatisfactory, as the recurrence and/or metastasis rate of OS is >30%. Additionally, in certain sarcomas such as early stage uterine leiomyosarcoma, adjuvant chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy) has shown no significant decrease in recurrence rates (4). The resistance of tumor cells to both radiotherapy and chemotherapy leads to a 5-year overall survival rate of <25% in patients with metastatic or recurrent OS (5). Rizzo et al (6) suggested that a more in-depth biological characterization was essential to comprehend the molecular biology of sarcomas and to improve identification of patients who could benefit from adjuvant therapy. Immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors have been developed as groundbreaking treatments for patients with cancer (7). More recently, chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy, which is known as an innovative form of immunotherapy, has garnered significant attention.

In 1993, Stancovski et al (8) made progress in the improvement of CAR-T cells. Nevertheless, the first generation of CAR-T cells used in initial clinical trials demonstrated limited survival rates in patients with cancer and a weak antitumor response. In 2013, Grupp et al (9) first used CD19-CAR-T cells to treat children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). During treatment, one child experienced serious complications, but the disease was eventually steadily alleviated. In 2017, the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two CAR-T cells targeting the CD19 protein, named Kymriah and Yescarta, for the treatment of ALL and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, respectively, and ~83% of patients treated with Kymriah achieved a response of ≤5 years after 3 months of treatment (10,11). In 2020, Astolfi et al (12) published a study indicating that the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes was the primary driver of sarcomas. The authors suggested that future therapeutic strategies should focus on targeting the key genetic drivers of sarcoma oncogenesis. Several clinical trials have been conducted to assess the efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy for the treatment of multiple myeloma, exploring various types of CAR-T cells, such as B-cell maturation antigen CAR-T cells (13-15), CD19-CAR-T cells (16) and CD138-CAR-T cells (17). The results have revealed favorable outcomes, with CAR-T cell therapy demonstrating significant inhibition of multiple myeloma, and the overall response rates ranging from 60 to 92% (13-17).

CAR-T cell therapy has become a groundbreaking treatment for hematological malignancies and multiple myeloma. However, recent research has focused on extending the use of CAR-T therapy to treat OS, which is a solid tumor and different from blood tumors. Although CAR-T cells have excellent effectiveness in hematological tumors and have been approved for use in hematological tumors, their use in the treatment of OS remains in its infancy, and there are still problems such as difficult homing and colonization of CAR-T cells, off-target effects, immune escape, immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) and cytokine release syndrome (CRS) (18). To address these issues, previous studies have tried a variety of CAR-T cells to treat OS and have obtained favorable results, for example, increased elimination of OS and reduced incidence of adverse effects (19-23).

The present study introduced in detail the structure of CAR-T cells and the influence of changing their structure on the therapeutic effect of CAR-T cells, which should help physicians to design CAR-T cells for optimal therapeutic effect (19,20). In addition, the current study provided an overview of all target antigens that can be used to treat OS and the results of the corresponding CAR-T cells (21-31). Compared with other reviews on CAR-T cell therapy for OS published in the literature, the present review described in detail the challenges that CAR-T cell therapy faces (32,33), the ways to solve these problems (34-41), and the advantages of combining radiotherapy (42), chemotherapy (43) and chemoradiotherapy (44), so that bone oncologists can have a more comprehensive understanding of CAR-T cell for OS.

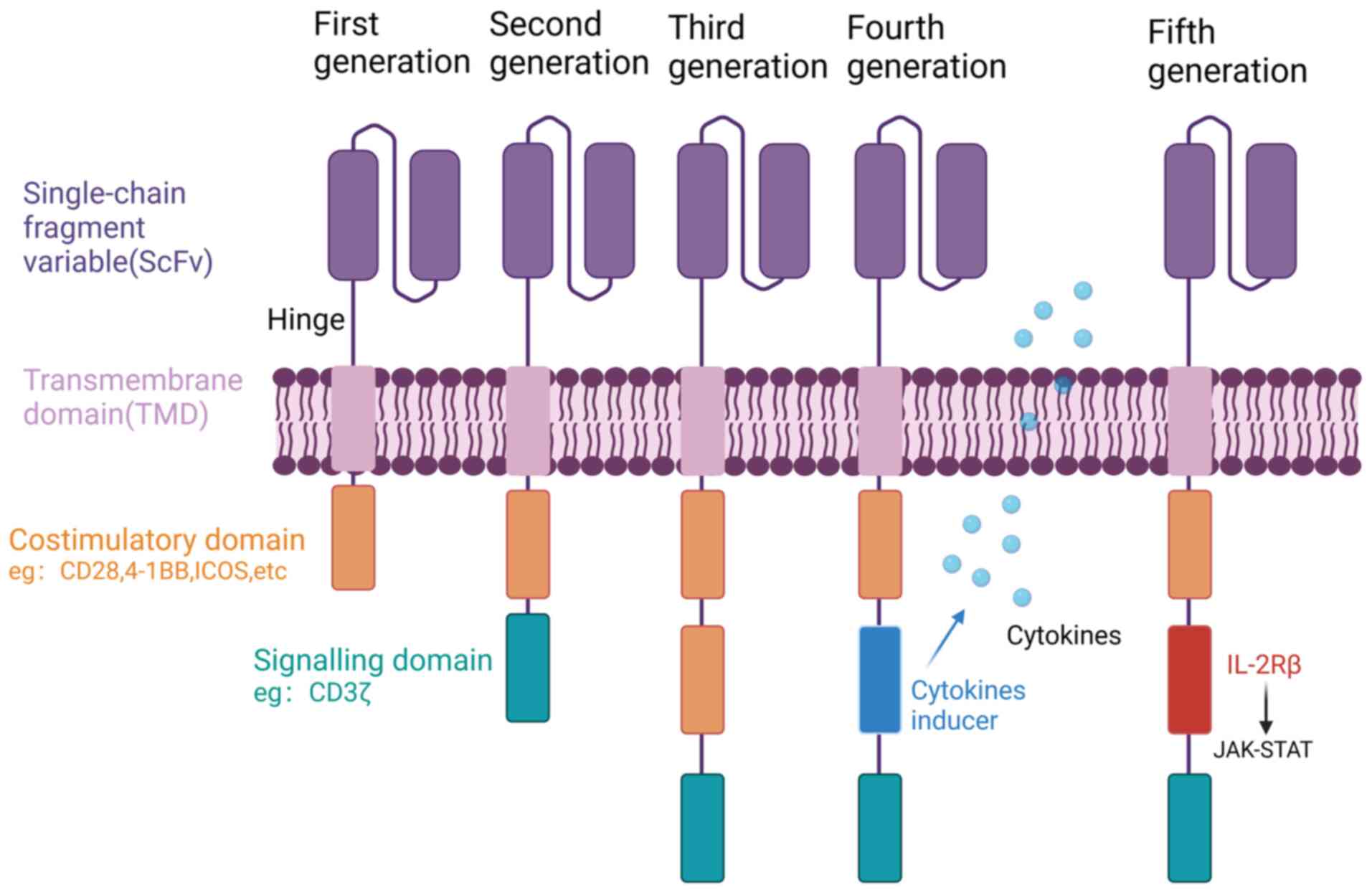

2. Structure of CAR-T cells

CAR-T cell therapy is a novel form of immunotherapy that utilizes genetic engineering techniques to modify and boost a patient's own immune cells outside the body (45). The therapy involves the use of a genetically engineered chimeric receptor called CAR, which is composed of various components, including an extracellular single-chain fragment variable (scFv), a hinge domain (HD), a transmembrane domain (TMD) and an intracellular domain (Fig. 1). The scFv is responsible for recognizing specific antigens on the surface of tumor cells, while the HD serves as a bridge between the scFv and TMD. The TMD anchors CAR to the membranes of T cells and promotes signal transduction into the cells, while the intracellular domain is responsible for T cell activation (19). First-generation CARs comprise a scFv and an intracellular CD3ζ activation domain. However, they have inadequate antitumor activity and proliferative capacity due to the absence of costimulatory signaling. To address this limitation, second-generation CARs have been developed. These incorporate an additional costimulatory domain, for example CD28, 4-1BB, OX40 or inducible costimulator (ICOS), which enhances their ability to proliferate and release a greater number of cytokines. At present, the marketable CAR-T cell products predominantly employ second-generation CAR structures. However, there have been advancements in the development of third-generation CARs, which incorporate two different costimulatory molecules, including CD28 and 4-1BB, to enhance their efficacy (46). Furthermore, fourth-generation CARs have emerged, which besides costimulatory domains, contain domains that regulate cytokine release. These cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-12, IL-18, IL-21 and IL-23, have the function of improving the TME and promoting the production of memory T cells, leading to increased persistence of CAR-T cells in vivo (47). Fifth-generation CARs incorporate IL-2Rβ membrane receptors, which offer a docking site for signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and trigger the activation of a Janus kinase (JAK)-STAT signaling domain. Additionally, these advanced CARs exhibit a combined activation of triple signals originating from the CD3ζ, costimulatory domain and the cytokine-inducing JAK-STAT3/5 pathway (48). CARs and T cells are assembled by lentiviral or other vectors to form CAR-T cells. When CAR-T cells specifically recognize the target antigen, the T cells are activated via the intracellular STD and play a tumor cell-eliminating role (45).

Traditional immunotherapies include monoclonal antibodies, tumor vaccines, oncolytic viruses, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and adoptive transfer of activated T cells and natural killer (NK) cells in vitro (49). Upon contact with tumor antigens, B cells produce highly homogeneous monoclonal antibodies that target only specific antigenic epitopes. Binding of the monoclonal antibodies to their target antigen can activate the complement system to promote the triggering of antibody-dependent cytotoxicity (50,51). Compared with monoclonal antibodies, CAR-T cells possess numerous advantages: Firstly, CAR-T cells can recognize tumor cells even when the expression of the targeted antigen is low, whereas monoclonal antibodies cannot do so; secondly, CAR-T cells are not only able to eliminate tumor cells directly, but also secrete cytokines such as IFN-γ, which enhance their antitumor effect; and thirdly, CAR-T cells are able to proliferate and maintain a long-lasting antitumor effect after infusion (52,53).

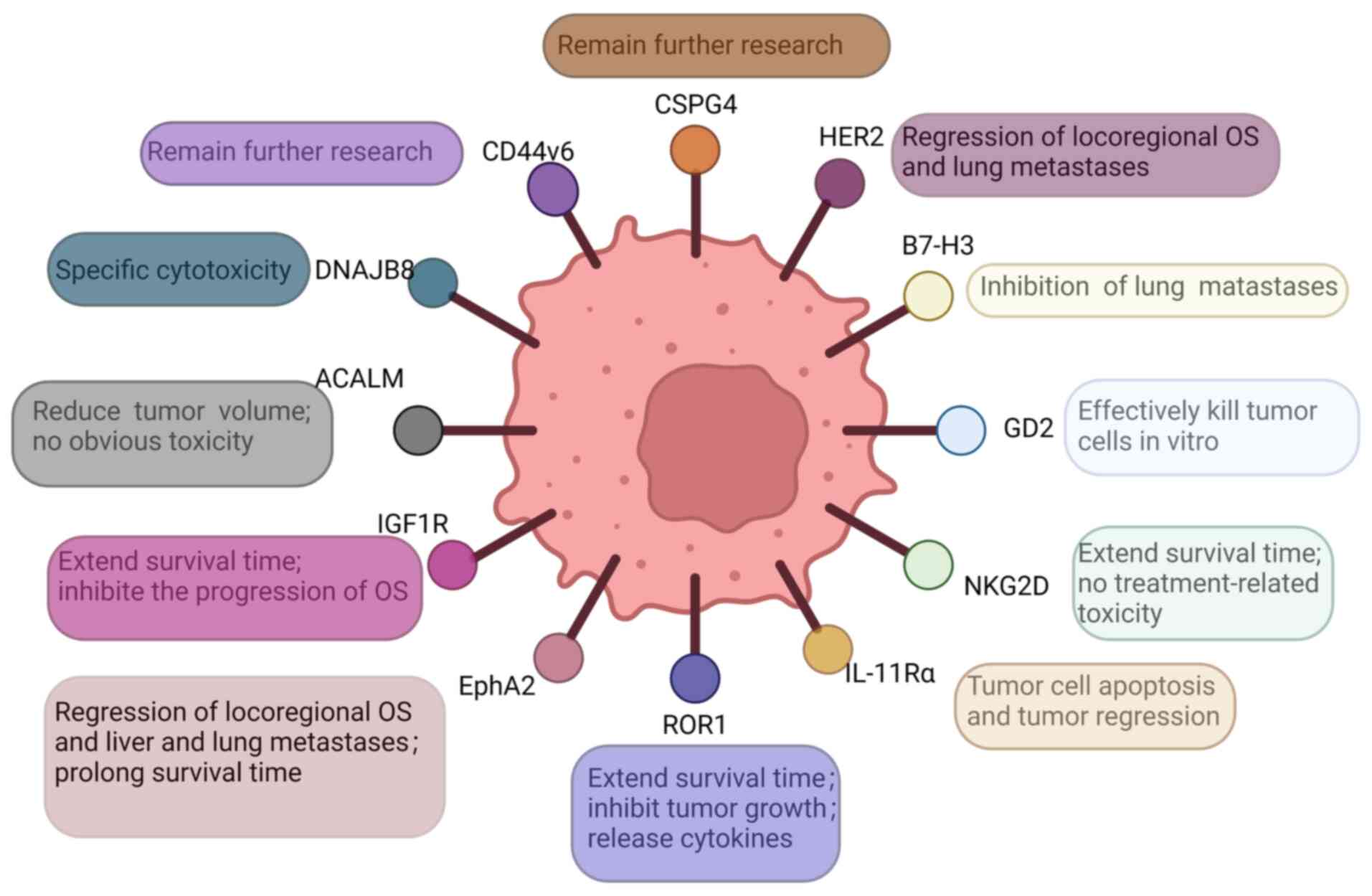

3. Antigen targets

Several target antigens for the treatment of OS have been reported. In the following sections, some of these antigens are presented, including DnaJ homolog subfamily B member 8 (DNAJB8), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), CD276, activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM, also known as CD166), EphA2, GD2, IL-11 receptor α chain (IL-11Rα), insulin-like growth factor type I receptor (IGF-1R), receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 (ROR1), NK group 2D (NKG2D), chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4) and CD44v6 (Fig. 2).

DNAJB8

DNAJB8 belongs to the heat shock protein 40 family. In health tissues, DNAJB8 is expressed only in the testis. In tumor tissues, DNAJB8 is preferentially expressed in cancer stem cells and has the function of cancer stem cell maintenance. Cancer stem cells can promote tumorigenesis, self-renewal and differentiation. Previous studies found that the overexpression of DNAJB8 increased the percentage of cells in the population representing cancer stem cells in renal cell carcinoma, and enhanced their ability to initiate tumors (21,54,55). Morita et al (21) proposed that DNAJB8-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes had higher eliminating activity against colorectal cancer stem cells and exhibited antitumor effects. Watanabe et al (56) successfully developed second-generation CARs targeting a peptide complex derived from DNAJB8, and confirmed that DNAJB8-CAR-T cells showed a target eliminating effect on OS cells, indicating that DNAJB8 could serve as a potential and promising target antigen of CAR-T cell for OS.

HER2

HER 2 is a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family, and plays an important role in cell proliferation (57). HER 2 is unique among the epidermal growth factor receptor family members due to its role in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation. Abnormalities in HER2 expression or function have been implicated in various malignancies, such as OS, where HER2 overexpression is associated with aggressive tumor growth. In the majority of OS cases, HER2 positivity is observed regardless of histological grade, and Abdou et al (58) indicated that positive expression of HER2 was significantly correlated with high-grade OS. Ahmed et al (52) demonstrated that HER2-CAR-T cells could eliminate HER2+ OS cells. A phase I/II clinical trial by Ahmed et al (22) revealed that patients with cancer could be transfused with safe doses of HER2-CAR-T cells that could reach the tumor and maintain it at low levels for >6 weeks in a dose-dependent manner. Thus, according to the aforementioned results, HER2 has been demonstrated to be an effective target antigen in CAR T-cell therapy for OS.

CD276

CD276 is an important immune checkpoint molecule belonging to the B7 family. It plays an essential role in modulating immune responses by exerting inhibitory effects on the activation, proliferation and cytokine production of T cells. Overexpression of CD276 is commonly observed in various cancer types, including OS, melanoma, Ewing sarcoma, non-small cell lung cancer and rhabdomyosarcoma (23). Picarda et al (23) reported that 91.8% of tumor cells in OS tissues expressed CD276, whereas the expression of CD276 in normal tissues was low. Accordingly, CD276 may be a potential target for the treatment of OS. CD276-CAR-T cells induced the regression of esophageal cancer and prolonged the survival time of mice, in addition to showing significant antitumor effects in radiotherapy-resistant prostate adenocarcinoma, ovarian cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor and neuroblastoma models (59-62). Previous studies have reported that CD276-CAR-T cells exhibit a dose-dependent antitumor activity and inhibit the development of spontaneous lung metastases in a mouse model of OS (63,64). Since CD276 has T-cell inhibitory effects, anti-CD276 CAR-T cells are a promising immunotherapy for the treatment of OS.

CD166

CD166 belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily and plays a role in a variety of biological activities, including neuronal growth, hematopoiesis and inflammatory responses (65). CD166 has been found in primary OS biopsy specimens, where its expression level is high (66). Flow cytometric analysis indicated that the expression of CD166 on OS cell lines varied and ranged from 36.9 to 96.7%, which suggested that CD166-CAR-T cells could be a promising treatment approach for OS (24). CD166-CAR-T cells exhibit complete activation upon encountering CD166+ OS cells, effectively eliminating OS cell lines in vitro. Encouragingly, when CD166-CAR-T cells were infused into mice, there was a notable regression of tumors without causing significant toxicity (24). This promising outcome highlights the potential of CD166-CAR-T cell therapy as a safe and effective method for treating OS. In addition, CD166-CAR-T cells showed strong cytotoxicity against colorectal cancer stem cells in vitro, thus they may be an effective method for the clinical treatment of colorectal cancer (67). According to the aforementioned studies, CD166 appears to be an essential target antigen in the treatment of OS.

EphA2

During embryonic development, EphA2 serves as a tyrosine kinase receptor for Eph signaling. However, in the later stages, EphA2 expression becomes predominantly limited to specific epithelial cells (68). Overexpression of EphA2 has been frequently detected in various cancer types, including OS, breast cancer, ovarian cancer and prostate adenocarcinoma (69,70). Compared with those in normal bone tissue, EphA2 protein levels were significantly elevated in OS bone tissue. Fritsche-Guenther et al (71) conducted a study where a correlation between the overexpression of EphA2 and the development of OS was observed. In an animal model of implanted OS, EphA2-CAR-T cells successfully eliminated EPHA2-overexpressing OS cells in immunodeficient mice and significantly prolonged mouse survival. Moreover, in animal models of metastatic OS, intravenously injected EphA2-CAR-T cells could target the tumors, and effectively eliminated OS liver and lung metastases (25). Based on the findings from the aforementioned studies, it can be concluded that EphA2 holds great potential as an effective and crucial target antigen for OS.

GD2

Gangliosides are glycated lipid molecules belonging to the sphingolipid group, which have the function of mediating tumor cell adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins and in directing signaling during cell death. However, their role in tumorigenesis remains unknown (72). GD2 expression has been observed to vary in tumor tissues among patients with sarcoma, central nervous system tumors and lung cancer (73). GD2-CAR-T cells have been revealed to exhibit antigen-dependent cytotoxicity against GD2-expressing lung cancer models both in vitro and in vivo (26). Long et al (74) found that third-generation GD2-CAR-T cells exhibited significant effectiveness in eliminating GD2+ OS cell lines in laboratory conditions, but showed limited efficacy in eliminating OS in vivo. Nevertheless, the phase I clinical trial (NCT02107963) has demonstrated the safety of increasing doses of third-generation GD2-CAR-T cells in patients with GD2+ OS (75), and bispecific antibodies targeting GD2 and HER2 have potent antitumor effects against OS in vitro and in vivo (76). According to the aforementioned studies, it can be concluded that GD2 holds promise as a valuable and effective target antigen for OS.

IL-11Rα

Previous studies have demonstrated that the expression of IL-11Rα on the cell surface is linked to unfavorable patient prognosis. IL-11Rα is activated by its ligand IL-11, which can activate multiple signaling cascades in its target cells and is considered an important regulator of bone homeostasis. IL-11 and IL-11R are both expressed in OS in situ and in lung metastases, and are markers of high-risk OS, while the expression of IL-11Rα is absent in neighboring health lung tissue (77,78). IL-11Rα-CAR-T cells are able to effectively eliminate OS cells in vitro, and have been observed to specifically target and accumulate in OS lung metastases following intravenous administration, while demonstrating no accumulation in the surrounding health lung tissue. The utilization of IL-11Rα-CAR-T cells for the treatment of OS led to notable apoptosis and regression of tumors in mice with lung metastases (27). These findings suggested that IL-11Rα serves as a promising, effective and crucial target antigen for OS.

IGF-1R

IGF-1 is a hormone with an insulin-like molecular structure, and overexpression of IGF-1 and its receptor (IGF-1R) has been associated with cancer development. At OS, elevated levels of IGF-1 and IGF-1R contribute to cancer development by promoting transformation, proliferation and metastasis, and by reducing susceptibility to apoptosis. Overexpression of IGF-1/IGF-1R also contributes to tumor cell survival and resistance to chemotherapy (79). It has been demonstrated that chemotherapy-resistant OS cell lines and primary OS tissues exhibit high expression of IGF-1R (80). Moreover, the application of IGF1R-CAR-T cells has been found to effectively impede the advancement of both systemic and localized OS in immunodeficient mice, leading to a significant extension in animal survival time (28). MicroRNA (miRNA or miR)-26a, miR-100 and miRNA-133a inhibit OS cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and increase tumor cell sensitivity to chemotherapy by targeting IGF1-R (81-83). In accordance with the results of the aforementioned studies, IGF1-R is a potential, effective and important target antigen for OS.

ROR1

ROR1, a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor, holds great importance in facilitating cancer cell migration, invasion and metastasis. Notably, elevated levels of ROR1 have been detected in both hematological malignancies and solid tumors, such as OS, Ewing sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. By contrast, ROR1 is not expressed in normal adult tissues (28,84). Previous studies have shown that anti-ROR1 monoclonal antibodies significantly block the metastasis of OS cells, and ROR1-CAR-T cells exhibit specific cytotoxicity against ROR1+ OS tissues and release sarcoma-specific cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-13 in vitro, while significantly inhibiting local and disseminated sarcoma growth. Furthermore, the administration of ROR1-CAR-T cells has demonstrated promising results in extending the survival time of local sarcoma models, suggesting that ROR1-CAR-T cell therapy holds potential as a management option for high-risk sarcomas (28,85). Consequently, CAR-T cells engineered by anti-ROR1 antigens are an effective measure for the treatment of OS.

NKG2D

NKG2D is a receptor responsible for activating NK cells. NKG2D ligand (NKG2DL) is expressed in various immunosuppressive cells present in the TME. This expression of NKG2DL enables tumor cells to evade immune surveillance by evading detection and elimination by NK and T cells. It has been reported that the binding of NKG2DL on tumor cells to NKG2D in NK cells could lead to cell-mediated cytotoxicity and destruction of target cells (29,86,87). NKG2D-CAR-T cell therapy has been investigated in phase II clinical trials (NCT02203825) for the treatment of hematological malignancies, and has shown promising results with no major safety concerns raised among the participants (88). Moreover, NKG2D-CAR-T cells exhibited an NKG2D-dependent mechanism to target solid tumors, including OS, and stomach, liver and cervical cancer, and demonstrated a potent antitumor activity (89-91). Fernández et al (29) indicated that NKG2D-CAR-T cells had a strong anti-OS activity. Thus, NKG2D holds great potential as an effective target antigen for OS.

CSPG4

CSPG4 is a cell surface proteoglycan that is under-expressed in healthy tissues but overexpressed in tumor cells and TME. It is involved in tumor progression by regulating intracellular signaling pathways related to tumor cell adhesion and migration. Several studies have reported that CSPG4 mediates multidrug resistance by stimulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which plays a critical role in promoting tumor cell proliferation and survival (30,92,93). The results of those studies identified that overexpression of CSPG4 was associated with shorter survival in patients with OS. Anti-CSPG4 monoclonal antibodies significantly inhibited the proliferation and migration of CSPG4+ OS cells and improved the efficacy of doxorubicin (30). Considering the results of the aforementioned studies, CSPG4 appears to be a potential, effective and important target antigen of CAR-T cells in the treatment of OS. However, clinical trials should be carried out to further assess their effectiveness.

CD44v6

CD44 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that can be expressed in its standard form (CD44s) and a variety of variants (CD44v). One of these variants is CD44v6, which regulates the extracellular matrix and inhibits tumor cell apoptosis (94,95). CD44v6 is expressed in several malignancies, including colorectal and breast cancer (96,97). A previous meta-analysis showed that overexpression of CD44v6 was associated with lower survival and metastasis in patients with OS (31). Nakajima et al (98) found that CD44v6 could be expressed in metastatic OS and was a protein of bone tumors. Although there are no studies in the literature focused on treating OS by targeting CD44v6, based on the outcomes of the aforementioned studies, CD44v6 appears to be a promising potential OS target antigen.

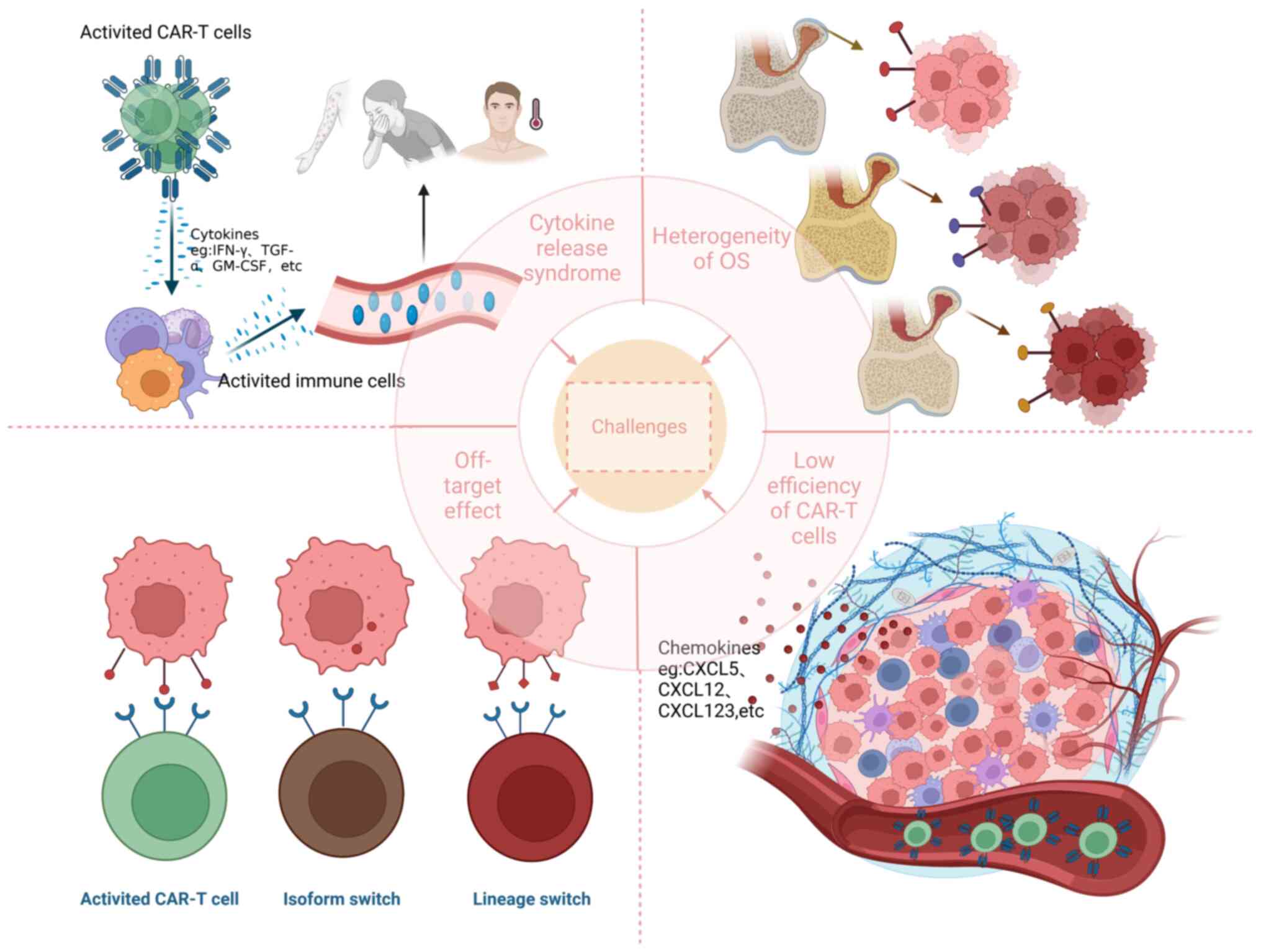

4. Challenges that CAR-T cell therapy faces

At present, CAR-T cell therapy for OS encounters several challenges, including off-target effect, inhibitory TME, CRS, low efficiency of CAR-T cells and heterogeneity of OS (Fig. 3).

Off-target effect

Tumor antigens can be classified into two types: i) Tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) and ii) tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) (99). TSAs are unique to cancer cells and are not found in normal healthy cells, which are ideal targets for immunotherapy, as they can be specifically targeted by the immune system without affecting normal cells. However, the expression of TSAs on the surface of OS cells is quite rare, which poses challenges in developing CAR-T cells that target these specific antigens. On the other hand, TAAs are present on both cancer cells and some healthy cells, but they are overexpressed in tumors. While they may not be as specific as TSAs, they still provide viable targets for immunotherapy. Nevertheless, the disadvantage of such CAR-T cells is that they can attack normal tissue cells and therefore have certain toxic side effects (100).

For instance, CD166 is not exclusively present in OS tissues, but is also found in certain normal tissues, including epithelial cells, smooth muscle cells and neurons (101,102). A patient with colorectal cancer who received numerous third-generation CAR-T cells targeting HER2 developed respiratory distress and cardiac arrest shortly after the infusion of the T cells, and succumbed to multiple organ failure 5 days later. It was therefore hypothesized that CAR-T cells recognize HER2 in the lung epithelium despite being expressed at low levels, causing pulmonary edema and cytokine storms that lead to adverse outcomes. This was the first fatal adverse event caused by CARs recognition of target antigens outside tumor tissues (57). Thus, it is essential to carefully evaluate the safety and effectiveness of CAR-T cell therapy.

Target antigens such as DNAJB8, HER2 and CD276 have been found on the surface of OS cells, and CAR-T cells targeting these antigens have been developed to specifically eliminate tumors (22,56,103). If the antigen of the tumor cell is lost or the density of the tumor antigen is reduced, the tumor cells cannot be targeted by CAR-T cells, and therefore the tumor cannot be effectively eradicated. Based on extensive clinical experience with CD19-CAR-T cells in acute B-lymphoblastic leukemia, the loss of CD19 antigen was postulated to occur through two distinct mechanisms: i) Isoform switching and ii) lineage switching. Isoform switching refers to the fact that mutated leukemia cells lack the epitope recognized by CD19-CAR-T cells, and/or CD19 is preferentially retained in the cell and therefore not recognized by T cells, while lineage switching refers to a phenomenon in the development of myeloid leukemia where tumor cells do not express CD19 in the presence of CD19-CARs (104). The same occurs with OS. Hsu et al (25) reported an increase in tumor cells lacking EphA2 expression following EphA2-CAR-T cell therapy for OS. Consequently, immune escape may seriously affect the antitumor effect of CAR-T cells.

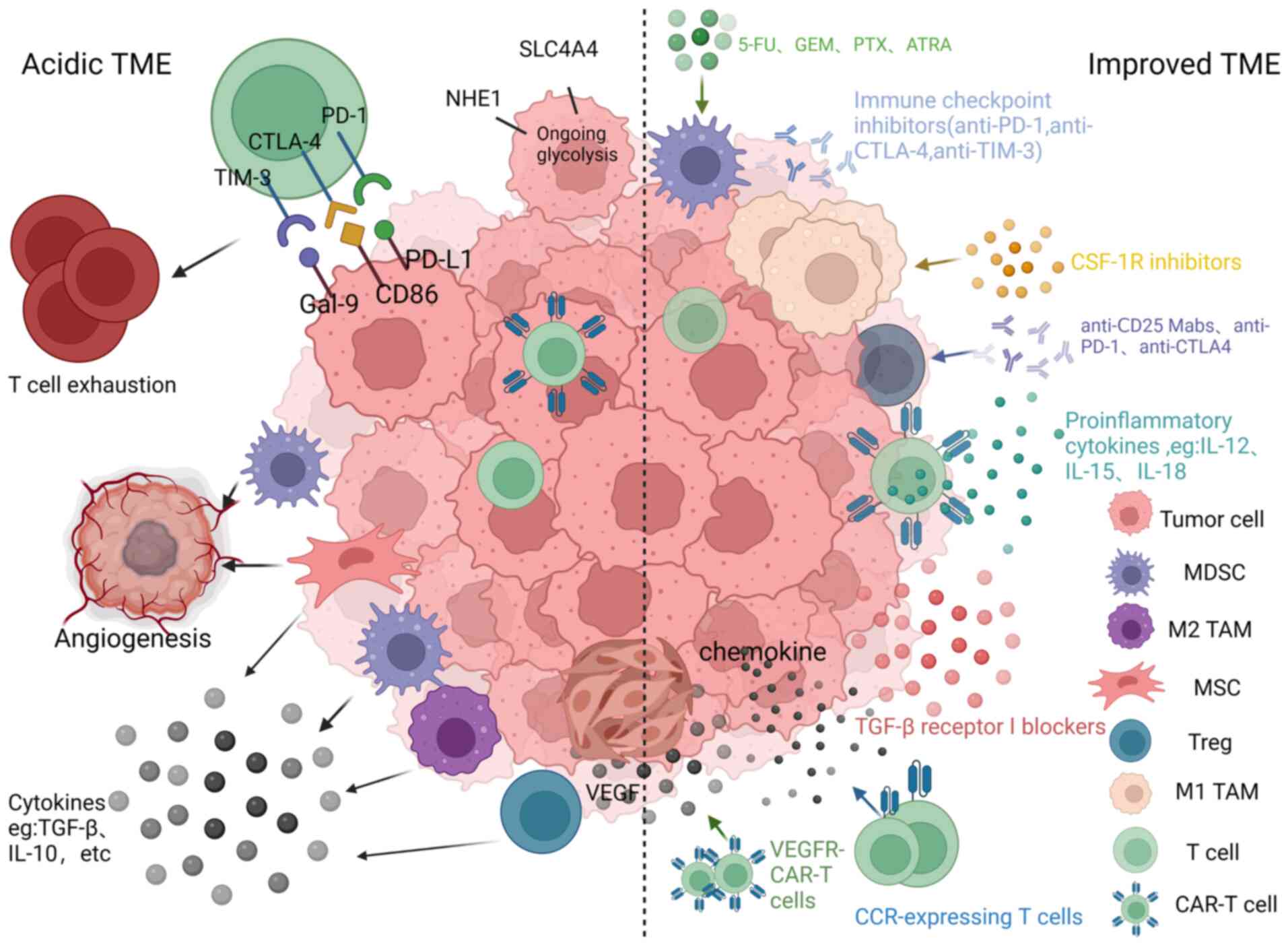

Inhibitory TME

CAR-T cells often encounter an inhibitory TME when infused into patients. This microenvironment can support angiogenesis, promote tumor progression and immune escape, and reduce the ability of CAR-T cells to proliferate and persist in vivo (Fig. 4) (105,106). The following subsection introduces specific immunosuppressive mechanisms.

Immune checkpoints

Immune checkpoints serve as immunosuppressive molecules that help to regulate the intensity and magnitude of the immune response. Immune checkpoints, including cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), TIM-3, Gal-9, programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) and PD ligand 1 (PD-L1), play a crucial role in promoting immune tolerance during tumor formation and development (107). PD-1 is expressed on activated effector T cells and other tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), including NK cells. Its presence inhibits immune responses in activated T cells, resulting in a suppressed immune response. This phenomenon, namely the fact that PD-1+ T cells are no longer cytotoxic and therefore cannot fight tumors, is called T cell exhaustion (108). Hashimoto et al (109) studied 16 samples of OS, and suggested that PD-1 and PD-L1 may be associated with tumor recurrence, metastasis and patient mortality. CTLA-4 was found to be expressed in OS cells. Administration of anti-CTLA-4 antibodies has been observed to augment the antitumor response of cytotoxic T cells (110,111). In addition, TIM-3 and Gal-9 are also expressed in OS tissues, and significantly promote the apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the TME of OS, and lead to poor prognosis in patients with OS (112,113). Thus, blocking immune checkpoints could further enhance the function of CAR-T cells.

Immunosuppressive cells

Within the TME, there are diverse cell populations that contribute to immune suppression, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Together with tumor cells, these cells orchestrate the control of the tumor and facilitate the production of inhibitory cytokines, chemokines and growth factors (114).

MDSCs are a prominent type of immune-suppressive cells that can hinder the antitumor function of CAR-T cells and can facilitate tumor angiogenesis. Additionally, MDSCs impede T cell proliferation by employing arginase, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, inducible nitric oxide synthase and IL-10 (115). Moreover, MDSCs can phagocytose antigens, degrade them and present them to CD8+ T cells that are specialized in recognizing such antigens. When MDSCs interact directly with T cells, MDSCs produce a substance called peroxynitrite. This substance modifies certain amino acids in the T-cell receptor and CD8+ molecules on the surface of T cells, which in turn impairs the response of T cells to specific antigen stimulation (115). The activity of MDSCs reduces the effectiveness of the immune response within the TME.

TAMs can be classified into two distinct categories: i) M1 TAMs, which inhibit tumor growth, and ii) M2 TAMs, which promote tumor growth (116). In the majority of cases, tumor cells have the ability to drive the differentiation of TAMs towards the immunosuppressive M2 subtype rather than the immuno-stimulatory M1 subtype. These M2 TAMs play an important role in promoting tumor formation and facilitating the spread of high-grade OS metastasis. This is achieved through the release of immunosuppressive soluble factors such as IL-10, TGF-β2 and C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 22 (117,118).

Tregs play a crucial role in inducing immunosuppression through various mechanisms. Firstly, Tregs express CTLA-4, which inhibits the maturation of antigen-presenting cells by reducing the expression of CD80/86, and hinders the activation of immune responses. Secondly, Tregs consume IL-2, a molecule necessary for the activation of effector T cells, including CD8+ T cells. As Tregs have high-affinity IL-2 receptors but produce minimal IL-2 themselves, this leads to a lack of IL-2 for effector T cells, resulting in their dysfunction. Lastly, Tregs secrete immunosuppressive cytokines like IL-10 and IL-35, directly inhibiting the activation of T cells (119).

Immunosuppressive cytokines

Immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10, IL-6 and TGF-β play an essential role in reducing the effectiveness of T cells in fighting against the tumor (120-122). Among them, the most critical inhibitory cytokine is TGF-β, which can act in tumors to stimulate tumor cells to spread further, metastasize and produce cytokines (123). In OS tissue, OS cells can directly release TGF-β1, and improved expression of TGF-β1 is associated with metastasis of high-grade OS (124). Moreover, elevated levels of IL-10 in tumor tissue hinder the production of IL-12 by dendritic cells, which inhibits the cytotoxic T cell response and the activation of NK cells (125). Furthermore, IL-10 hinders the antigen presentation process and suppresses the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by antigen-presenting cells, which promotes immune tolerance. Elevated levels of IL-10 not only exhibit strong immunosuppressive activity but also contribute to tumor cell proliferation and increased resistance to chemotherapy (126). IL-6 acts not only internally in tumor cells to promote tumor cell proliferation, survival and metastasis, but also externally in other cells present in the TME to promote tumor angiogenesis and evade immune surveillance (127).

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

MSCs are considered the utmost important factor in promoting OS migration in the TME (128). On the one hand, the interaction between MSCs and tumor cells facilitates angiogenesis and ultimately leads to the formation of new blood vessel networks in tumor tissues (129,130). However, the newly formed blood vessels are often structurally and morphologically abnormal, leading to persistent hypoxia, acidic TME and invasion of tumor cells into blood vessels, which facilitates tumor cell metastasis, and impairs CAR-T cell survival (131). For example, in a rat model of OS, intravenous administration of MSCs had no effect on tumor growth but significantly promoted metastasis to the lung (132). MSCs could stimulate the proliferation of CD4+ T cells and Tregs, while simultaneously causing a decrease in CD8+ T cells (133). Moreover, certain cytokines secreted by MSCs, such as TGF-β, may promote tumor immune escape and debilitate the antitumor immune response (129). Furthermore, MSCs induce the upregulation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and PD-L1, which are both involved in the immunosuppression of tumors, leading to inhibition of the efficacy of CAR-T cells (133).

Hypoxia and pH

Tissue hypoxia is a characteristic of the OS microenvironment. Hypoxia, or low oxygen conditions, within the TME plays an important role in chemotherapy resistance, tumor advancement and metastasis in OS. Firstly, hypoxia could regulate OS by primarily activating the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) (134). HIF is a heterodimer composed of α and β subunits. HIF expression is increased in OS and has the function of regulating the cellular adaptive response to hypoxia by promoting the transcription of various hypoxia-inducible genes. There are three subtypes of HIF-α, namely HIF-1α, HIF-2α and HIF-3α. Among these HIFs, the most important is HIF-1α (135), which promotes the distant metastasis of OS, and the invasion and proliferation of the OS MG63 and U2OS cell lines, which are inhibited when the expression of HIF-1α is reduced (136,137).

Secondly, immune-inflamed 'hot' tumors are characterized by an abundance of CD8+ T cells and the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. By contrast, immune desert 'cold' tumors lack CD8+ T cells and instead harbor populations of immunosuppressive cells such as TAMs, MDSCs and Tregs (138). Hypoxia transforms solid tumors into immune deserts by decreasing the ratio of antitumor M1 TAMs to tumor-friendly M2 TAMs (139). Furthermore, hypoxic tumors secrete chemokines such as CXC motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)12, CCL5 and CCL28, which attract immunosuppressive populations such as Tregs and MDSCs (140). Additionally, the oxygen-deprived environment hinders the utilization of glucose by CAR-T cells, impeding their expansion. Otherwise, CAR-T cells would produce abundant lactic acid through glycolysis, and the increased acidity in the TME would inhibit T lymphocyte function, activate MSCs and ultimately promote OS progression (140,141). Other pH-regulatory enzymes induced under hypoxia, such as carbonic anhydrase, Na/H exchanger, solute carrier family 4 member 4 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, are responsible for TME acidification and tryptophan deficiency, all of which inhibit the activity of T cells (142-144).

Extracellular vesicles

Extracellular vesicles are membrane-bound vesicles that cells release into the surrounding extracellular matrix. They contain various essential signaling molecules, including proteins, nucleic acids, enzymes and other soluble factors. These vesicles play a crucial role in cell communication, angiogenesis and tumor cell proliferation. They achieve this by exchanging information with target cells. Yang et al (145) demonstrated that extracellular vesicles were involved in the progression and spread of OS. Tumor-derived exosomes have been shown in multiple studies to hinder the function of T and NK cells through diverse mechanisms, including induction of T cell apoptosis, enabling OS cells to evade immune surveillance (146). Prudowsky and Yustein (147) demonstrated that extracellular vesicles facilitated the transfer of multidrug resistance 1 mRNA between OS cells, thereby enhancing resistance to Adriamycin.

Metabolism

In the TME, CAR-T cells require sufficient nutrients and energy substances, including glucose, amino acids and glutamine, which are also necessary for tumor cell metabolism, for exerting their antitumor effect. However, tumor cells consume energy more rapidly than T cells, which inhibits T cell proliferation and function due to insufficient nutrient requirements (148).

First, OS cells promote c-Myc expression through platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)/PDGF receptor β signaling and increase aerobic glycolysis under aerobic conditions (149). Second, TME may also be deprived of essential amino acids. In mouse models of colon and lung cancer, MDSCs with high arginase activity were locally present in tumors and spleens, consuming arginine, and inhibiting T-cell proliferation and cytokine production (150). Arginase-1 is an amino acid-degrading enzyme commonly expressed in the TME, which promotes L-arginine metabolism and inhibits T-lymphocyte responses (151). Third, glutamine is another important factor affecting T-cell function. Since glutamine is required for T cell proliferation, decreased glutamine metabolism in T cells reduces the expression of metabolic regulators and impedes T cell activation (152,153). Thus, it is of utmost importance to maintain a metabolic equilibrium between T and tumor cells, which is vital for the successful management of tumors.

CRS

CRS, a severe adverse effect linked to CAR-T cell therapy, is an inflammatory syndrome triggered by the production of several cytokines by CAR-T cells. This syndrome is considered to be associated with high antitumor activity and tumor burden. The cytokines implicated in CRS consist of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-8, IL-10 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (154,155). The initial indication of CRS typically manifests as fever, which can emerge within hours to days following the infusion of cells. After the initial fever, patients may experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, skin rash, delirium, low blood pressure and even severe multi-organ failure (99). A previous study reported serious adverse events, even fatal, caused by CRS (57).

T cell inefficiency

CAR-T cell expansion ability and persistence

Clinical evidence indicates that the expandability and persistence of T cells after infusion are crucial factors for achieving effective cancer therapy (156). However, during CAR-T cell therapy for OS, T cells may become depleted due to various reasons, rendering them unable to fulfill their intended function. A previous study has indicated that a transcription factor known as nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A number 1 (NR4A1) plays an important role in T cell fatigue. In mouse models with tumor-bearing mice, the injection of NR4A1-CAR-T cells has shown a remarkable ability to impede tumor growth (157). Furthermore, when antigens stimulate naive T cells, they undergo proliferation and differentiate into memory T cells. This process involves several stages, starting with naive T cells and progressing to stem cell memory T cells, central memory T cells, effector memory T cells and finally effector T cells. In mice, it has been observed that the less differentiated subtypes, including naive T cells, stem cell memory T cells and central memory T cells, consistently exhibit higher expansion, longer persistence and stronger antitumor abilities compared with the more differentiated effector memory T cells and finally effector T cells (158). Thus, naive T cells, stem cell memory T cells, central memory T cells, can be employed to augment the antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cells during CAR-T cell production.

CAR-T cell infiltration capability

CAR-T cells targeting solid tumors must penetrate the extracellular matrix and immunosuppressive TME to reach the tumor (159). Some chemokines secreted by solid tumors, including CXCL123, CXCL12 and CXCL5, impede the movement and entry of T cells into tumor sites; however, the lack of appropriate chemokine receptors on T cells hampers their ability to infiltrate the tumor region (160-162). The presence of tumor cells diminishes the quantity and effectiveness of CAR-T cells, significantly compromising their ability to eliminate tumor cells. Hence, enhancing the penetration capacity of CAR-T cells is crucial.

Heterogeneity of OS

In contrast to hematological tumors, OS is a type of solid tumor. The antigens targeted by immunotherapy on solid tumors typically exhibit heterogeneity, varying not only between different types of solid tumors but also between the primary and metastatic stages of the same tumor (163). Thus, careful selection of appropriate TAAs plays a vital role in achieving an effective anti-OS response.

5. Strategies to enhance the efficacy of CAR-T cells

To increase the eliminating efficiency of CAR-T cells and reduce their side effects, a number of measures have been taken based on the shortcomings of CAR-T cells. These measures are mainly aimed at promoting the effect of CAR-T cells, including optimizing CAR-T cell structure, improving the immunological microenvironment, increasing T cell efficiency and preventing CRS.

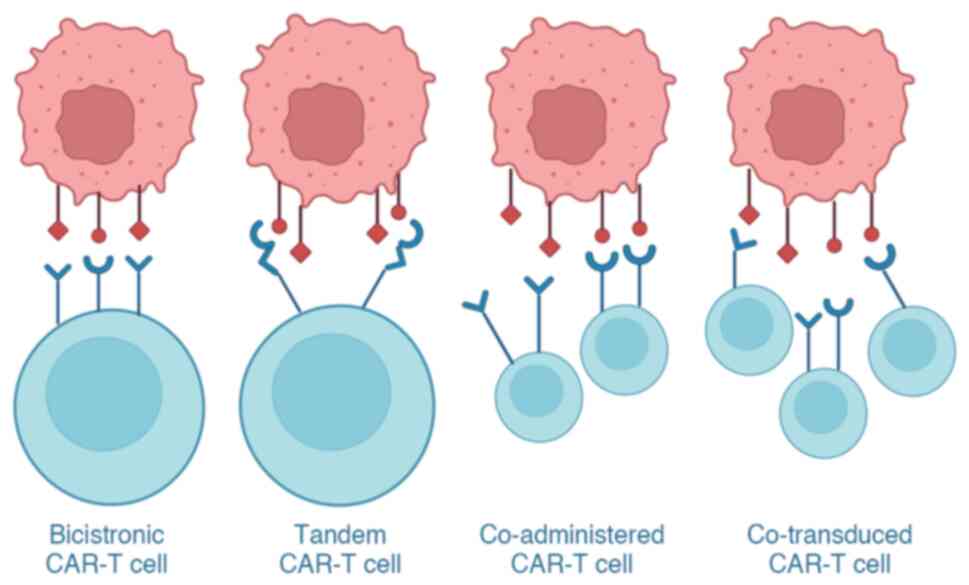

Optimization of CAR-T cell structure

The utilization of CAR-T cell therapy comes with the inherent risk of off-target effects due to the fact that the TAAs, which CAR-T cells recognize, are not restricted to tumor cells, but can also be detected in normal tissue cells. Additionally, the efficacy of CAR-T cells can be directly reduced by the escape, depletion or loss of tumor antigens. To address these challenges, clinical trials are currently exploring the use of CAR-T cells with two or three target antigens to improve their effectiveness. Therefore, enhancing the anti-OS effect of CAR-T cells could be achieved by optimizing their structure.

Optimization of the antigen recognition domain (ARD)

The main function of the extracellular domain of CAR-T cells is to recognize tumor cell antigens. Researchers have improved the extracellular domain of CAR-T cells to tackle the issues of tumor antigen escape, reduction, loss and off-target effects (164,165). As a result, numerous CAR-T cells have been constructed, including dual-targeted, triple-targeted and tandem CAR-T cells (Fig. 5). Dual- and triple-targeted CAR-T cells refer to the design of two or three separate CARs on a T lymphocyte, where each CAR is specific for different antigens and thus has dual or triple targeting ability. Tandem CAR-T cells are defined as those with two different scFv regions in a single CAR, targeting different antigens.

Tian et al (164) demonstrated that, by utilizing dual-target CAR-T cells, which could target two TAAs, it was possible to overcome the heterogeneous expression of these antigens in solid tumors. This approach resulted in improved persistence and enhanced resistance to exhaustion. Moreover, recent research has indicated that the use of innovative tandem CAR-T cells, which target both IL-13Rα2 and EphA2, exhibits significantly higher efficacy in eliminating glioblastoma cells in both laboratory settings and animal models, compared with CAR-T cells that target only one of these antigens (165). To clarify how multi-target CAR-T cells work (for example, whether dual-targeted CAR-T cells are able to eliminate tumors by recognizing only one target antigen, or whether they must recognize both), Boolean logical operations, including 'AND', 'OR' and 'NOT' have been used. CAR-T cells with 'AND' are activated only when both target antigens are recognized, while CAR-T cells with 'OR' can be activated by recognizing either target antigen, and CAR-T cells with 'NOT' avoid eliminating normal cells by stopping their action when a particular antigen is recognized (166). Therefore, the logical gates 'AND', 'OR' and 'NOT' in Boolean logic can improve the recognition and elimination ability of CAR-T cells toward tumor cells and effectively avoid off-target effects. Thus, enhancing the eliminating capacity of CAR-T cells against tumor cells can be achieved by optimizing the ARD, which has been demonstrated to be an effective approach.

Optimization of the HD

The HD or spacer region is located in the extracellular region of CARs. The HD mainly plays the following roles: i) It increases the flexibility of the ARD, which is conducive to target antigen recognition; and ii) both the hinge length and type affect the strength of the activation signal of the CARs and the formation of immune synapses (167,168). To a certain extent, the size of the HD in CAR can be adjusted, reducing the obstacle created by the spatial distance between target and CAR-T cells (169). A long hinge has the advantage of favorable flexibility, which favors the capture of target epitopes close to the membrane with the ARD (170,171). Hudecek et al (172) demonstrated that enhancing the length of the HD could enhance the ability of CAR-T cells to recognize tumors, but a short hinge has the advantage of facilitating the binding of target epitopes far from the membrane (173). The main sources of hinge mentioned in the literature are CD8, CD28, immunoglobulin (Ig)G1, IgG4 and IgD (172,174). Previous studies have revealed that variations in the HD can impact the elimination efficiency, longevity and cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells towards healthy cells (167,175-178). Therefore, optimizing the HD holds great importance for improving the antitumor effect of CAR-T cells.

Optimization of the TMD

The TMD serves to anchor CARs to the cell membrane of T lymphocytes. The TMD is normally formed by CD28, CD8, CD4 and ICOS (179). The TMD has been identified to increase the stability and mobility of CARs (180,181). In first-generation CARs, TMD derived from CD247 promotes T lymphocyte activation (180). The commonly used second- and third-generation CD8- and CD28-derived TMD further improves the stability, mobility and efficacy of CARs compared with the CD247-derived TMD (181-183). Fujiwara et al (184) reported that altering the structure of the TMD affected the expression levels and activity of CARs. The authors also found that modifying the TMD could modulate the function of CAR-T cells without impacting the antigen-binding properties of the ARD or the signal transduction properties of the signal transduction domain (STD). Although previous studies have improved the persistence of T cells, inhibited tumor growth and reduced the incidence of complications such as CRS by optimizing the structure of the TMD of CAR, the role of the TMD needs further investigation (181,182,185). Thus, ongoing optimization of the TMD structure is important for improving the efficacy of CAR-T cells.

Optimization of the intracellular domain

The intracellular domain of CAR-T cells comprises both costimulatory molecules and a STD. Huang et al (186) observed that the costimulation domains significantly enhanced the expansion and long-term persistence of CAR-T cells for therapeutic purposes. The costimulatory domains significantly contributed to the proliferation and persistence of CAR-T cells for therapy. The TNF receptor (CD137, CD27 and OX40) (53,187,188) and CD28 (189,190) families are the most commonly used costimulatory molecules. Exploring the activation mechanism of costimulatory molecules is a crucial approach to identify optimization strategies for CAR-T cells. Currently, CD28 and CD137 are FDA-approved costimulatory molecules for CAR-T cells (191). Although the effectiveness of CAR-T cells with these two costimulatory molecules in treating hematological tumors is similar, there are differences in the eliminating effect, duration and mechanism of CAR-T cells. Specifically, CAR-T cells using CD28 as a costimulatory molecule are characterized by rapid eliminating and high efficacy but low durability (192,193), while CAR-T cells using CD137 as a costimulatory molecule are characterized by moderate and weak eliminating but high durability (193). Several studies have attempted to optimize costimulatory molecules to enhance T lymphocyte activity. Guedan et al (194) identified an amino acid residue in CD28 that promoted T lymphocyte exhaustion. The authors replaced phenylalanine with asparagine in CD28, which delayed T cell exhaustion, increased durability and improved antitumor efficacy. Further studies should combine the advantages and disadvantages of the costimulatory molecules CD28 and CD137, and redesign them to increase antitumor activity. Overall, the signals provided by costimulatory molecules during CAR-T cell activation are critical for T lymphocyte metabolism, survival and efficacy. Therefore, a detailed study of the mechanism of costimulatory molecules would be helpful to construct CAR-T cells with high efficacy, long endurance and low side effects to improve their effect on tumor treatment.

The STD primarily consists of CD247, which is mainly derived from the T cell receptor complex. CD247 contains three immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) and is present in almost all CAR structures. Van der Merwe and Dushek (195) reported that the ITAM was an immune receptor activation domain consisting of two Yxx (I/L) and 6-8 amino acids. Gaud et al (196) found that Src family lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase phosphorylates the tyrosine in the ITAM, which then recruits ZAP70 kinase and further activates signaling molecules such as T lymphocyte linker protein and phospholipase C-γ. In addition, Feucht et al (197) found that altering the second and third ITAMs in CD247 increased the efficacy and durability of CAR-T cells. James (198) noticed that augmenting the number of ITAMs in a second-generation CAR led to an enhancement in the activity of CAR-T cells. Thus, the localization and quantity of ITAMs can influence the functionality of CAR-T cells. A comprehensive investigation of the STD and its associated functions in CAR should therefore help to develop new CAR-T cells and improve their effectiveness against tumors.

To improve the efficacy of tumor cell eradication, various studies have experimented with co-transducing CAR-T cells and employing a combination of two distinct single-targeted CAR-T cell therapies (199-201) (Fig. 5). Co-transduced CAR-T cells are T cells that have been co-transduced with two different lentiviral vectors, with some of the resulting T cells expressing both CARs and some expressing only one CAR (199). Ghorashian et al (200) employed co-transduced CAR-T cells for treating patients with relapsed or refractory ALL, and found that co-transduced CAR-T cells exhibited favorable safety profiles, robust expansion capacity and promising early efficacy. Dual CAR-T cell therapy refers to the administration of two single-targeted CAR-T cells, either simultaneously or sequentially, with each CAR-T cell targeting a distinct antigen (Fig. 5). It has been demonstrated that the sequential infusion of distinct CAR-T cells, each designed to target specific tumor antigens, exhibited promising antitumor effects in clinical trials (201). These findings suggested that the sequential injection of different CAR-T cells may be an effective strategy to combat tumors.

Improvement of the TME

There are numerous ways of improving the TME, and the mechanisms involved are described below (Fig. 4).

Combination with checkpoint inhibitors

Checkpoint inhibitors increase the immune activity of CAR-T cells, reducing immunosuppression caused by increased cytokines and loss of target antigens, leading to activation of inhibited T cells (202). Zheng et al (35) reported that the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab effectively stopped the spread of OS in mice by boosting the population of CD8+ cells and enhancing the cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, PD-1 treatment not only decreased the number of tumor cells and promoted apoptosis in lung metastases of OS, but also made macrophages change from an M2 to an M1 phenotype, resulting in the regression of lung metastases in OS (203). Moreover, Rafiq et al (204) have engineered CAR-T cells capable of producing scFv to block PD-1, and preclinical studies have indicated that these CAR-T cells demonstrate equivalent or improved efficacy compared with combination therapy involving CAR-T cells and PD-1 inhibitors. Kenderian et al (205) reported that immune checkpoint blockers such as TIM-3 combined with CAR T-cell therapy could have synergistic antitumor effects.

Targeting immunosuppressive cells

Immunosuppressive cells present in the TME, such as MDSCs, Tregs and TAMs, hinder the antitumor effectiveness of CAR-T cells.

MDSCs play a critical role as immunosuppressive cells and can be effectively targeted through the following approaches: i) Depletion of MDSCs in the bloodstream and at tumor infiltration sites by using low-dose chemotherapy. Drugs such as 5-fluorouracil, paclitaxel and gemcitabine have been shown to effectively reduce MDSC populations. Combining this low-dose chemotherapy with CAR-T-cell therapy can enhance antitumor responses. By targeting and depleting MDSCs, this combination therapy holds great potential in improving the outcomes of cancer treatment (206-209); ii) preventing the aggregation of MDSCs. A previous study revealed a positive association between MDSC levels and IL-18, indicating that IL-18 promoted the migration of MDSCs into tumor tissue. By administering anti-IL-18 treatment, a significant reduction in MDSCs in both tumors and peripheral blood was observed. This finding suggested that targeting IL-18 could be a favorable approach to improve the effectiveness of immunotherapy in patients with OS (34); iii) counteracting the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs by the use of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA). Administering this compound to mice with OS was found to effectively eliminate MDSCs and reduce their inhibitory impact. Additionally, combining ATRA with GD2-CAR-T cell therapy in the management of OS demonstrated significant improvements in antitumor efficacy. This combination approach holds great potential in enhancing the immune response against OS and improving the overall outcome of treatment (74); and iv) promoting the differentiation of MDSCs into a non-suppressive immune state. ATRA was found to have a direct effect on MDSCs, inducing their differentiation into mature myeloid cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. This process led to a significant decrease in the inhibitory effect of MDSCs on T cells, ultimately promoting an improved immune response (210).

Tregs are another type of immunosuppressive cells. One of the primary approaches in Tregs-based immunotherapy is decreasing the population of Tregs, for example, by applying anti-CD25 monoclonal antibodies to eliminate CD4+ and CD25+ Tregs, and to facilitate the specific eliminating effect of CD8+ T cells in OS. The second approach involves preventing the immunosuppressive effects of Tregs, which express certain proteins that suppress the immune response. These proteins, such as CTLA-4 and PD-L1, can be blocked using specific inhibitors. The third option aims to enhance the activity of effector T cells, which is responsible for suppressing the suppressive effects of Tregs. In immune surveillance, checkpoints inhibit the activation of T cells, leading to the inability of TILs to eliminate cancer cells in OS. Yoshida et al (211) found that checkpoint inhibitors could restore T cell-mediated antitumor responses by releasing the brake and engaging major histocompatibility complex molecules.

TAMs are also immunosuppressive cells in the TME, and targeting TAMs is mainly achieved by switching subtype and reducing the number of TAMs. Blocking the receptor of colony-stimulating factor 1, an important regulator of TAMs recruitment, not only decreases TAMs recruitment to tumors but also enhances the differentiation of TAMs into a proinflammatory M1 phenotype, leading to an increased intratumoral M1/M2 ratio in mice (212). Furthermore, it was revealed that low-dose radiotherapy could reprogram TAMs into M1 TAMs (213,214). Moreover, certain antigens expressed on immunosuppressive cells within the TME could be targeted to eradicate both tumor and immunosuppressive cells, as demonstrated by the specific action of CD123-CAR-T cells against tumor cells and TAMs in Hodgkin lymphoma (215).

Targeting immunosuppressive cytokines

Neutralizing TGF-β, a critical tumor suppressive cytokine, has the potential to amplify the antitumor immune response mediated by CD8+ T cells. Several strategies have been explored based on this concept. Inhibition of TGF-β1 signaling using vactosertib, a TGF-β receptor (TGF-βR)1 inhibitor, has demonstrated a significant reduction in OS cell proliferation both in laboratory settings and in animal models (216). Wallace et al (36) observed that inhibiting TGF-βR led to a significant improvement in the efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy in animal models of solid tumors. Tang et al (217) demonstrated that removing TGF-βR 2 by using genome editing techniques reduced exhaustion in CAR-T cells and enhanced the effectiveness of mesothelin-CAR-T cells against ovarian cancer cells.

Production of proinflammatory cytokines

Another approach to increase the efficiency of CAR-T cells is to induce them to produce proinflammatory cytokines. Armored CAR-T cells have been hereditarily engineered to produce proinflammatory cytokines, aiming to shield them from the inhibitory effects of the TME. IL-18-secreting CAR-T cells, for example, exhibited increased expansion, persistence and antitumor cytotoxicity compared with CAR-T cells that target only tumor antigens. Additionally, these enhanced CAR-T cells not only altered the TME in mouse lymphomas but also administered IL-18 directly to the tumors. This approach facilitated the recruitment and activation of native antitumor immune effector cells, leading to a robust and comprehensive endogenous antitumor immune response (39). In addition, CAR-T cells that could secrete cytokines such as IL-15 (218) and IL-12 (219) demonstrated amplified proinflammatory capabilities. Thus, CAR-T cells secreting proinflammatory cytokines would be an ideal solution for treating OS.

Regulation of the metabolism

CAR-T cells produce abundant lactate through glycolysis, which increases the acidity of the TME and inhibits T lymphocyte function. Small molecules and metabolites such as cytokines, the glucose analogue 2-deoxy-D-glucose, L-arginine and carnosine have been revealed to affect T-cell metabolism and differentiation. Numerous studies have investigated and confirmed the ability of the cytokines IL-7, IL-15 and IL-21 to limit or interfere with glycolysis (220,221). 2-Deoxy-D-glucose is a glycolytic inhibitor. During in vitro expansion, CD8+ T cells change their differentiation direction in the presence of 2-deoxy-D-glucose to form more memory cells, resulting in long-lasting antitumor function (222). Intracellular L-arginine is significantly reduced after activation of naive T cells, and the additional incorporation of L-arginine into the culture medium causes a shift in metabolism from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation. It also increases the level of stem cell memory T cells, resulting in greater antitumor activity (223). In another study, carnosine was found to limit the acidification of extracellular fluid, changing the metabolism of activated T cells from glycolytic to aerobic, ultimately leading to an improved antitumor function of T cells. In addition, transiently elevating the level of carnosine in the culture medium increased lentivirus gene expression (224). Therefore, these results provided ideas to increase the therapeutic efficacy of CAR-T-cell therapy.

Prevention and treatment of CRS

According to the criteria used to evaluate adverse reactions, CRS has been classified into five levels, ranging from mild reactions/grade 1 to mortality/grade 5. The extent of CRS triggered by CAR-T cells is directly associated with the expansion of CAR-T cells and the concentration of IL-6 in the bloodstream (225). Turtle et al (226) conducted a study that revealed that tocilizumab, an anti-human IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, was the primary management option for patients experiencing moderate to severe CRS. Li et al (10) emphasized the importance of timely tocilizumab treatment for elderly patients with grade 3 or 2 CRS and comorbidities to prevent severe CRS (grade 4 and 5), with the majority of patients achieving rapid remission post-tocilizumab. Davila et al (227) observed that administering high-dose corticosteroids could effectively impede the proliferation and persistence of CAR-T cells in vivo. As a result, high-dose steroids could also be employed as a management alternative for patients experiencing CRS. However, it is essential to highlight that high-dose steroids are typically reserved for patients with severe and life-threatening CRS who have not responded to tocilizumab treatment.

A previous study constructed inhibitory CARs (iCARs) based on the inhibitory molecules CTLA-4 or PD-1, and showed that these iCARs could block T cell responses activated by their endogenous T cell receptors or activated CARs. This inhibitory effect was transient, and, in the absence of an inhibitory signal, suppressed T cells could be reactivated when exposed to an activating signal. Thus, iCARs may allow T cells to target tumor cells while avoiding attacking normal tissue (37). Moreover, an interesting and feasible approach is the use the tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib, which, in preclinical models, efficiently and temporarily hindered the activation of CAR-T cells. Brief treatment with dasatinib early after infusion of CAR-T cells could prevent lethal CRS in mice (228).

It could therefore be inferred that high-grade CRS may be reversed through early and aggressive treatment. Notably, resolution of CRS could result in an anti-CRS syndrome characterized by hypothermia and bradycardia, accompanied by alterations in cytokine levels (229). Therefore, patients should be monitored for vital signs even after successful CRS treatment.

CAR-T cell targeting of tumor blood vessels

Tumor blood vessels, by being highly perfused, have a crucial role in the progression and metastasis of OS. Thus, CAR-T cells targeting OS blood vessels have attracted the attention of researchers. Previous studies have revealed the existence of pro-angiogenic growth factors in the TME, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), with tumor cells exhibiting overexpression of receptors for these factors, which is strongly correlated with adverse prognosis and tumor metastasis (38). Fukumura et al (230) found that VEGFR-2 was overexpressed in some tumor stromal cells. CARs targeting VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 have demonstrated promising efficacy in disrupting tumor vasculature and reducing tumor cell proliferation by limiting nutrient and oxygen delivery, and preserving normal tissue (231,232).

Improving the effectiveness of T cells

Promoting the settlement of CAR-T cells

The TME in OS tissue is characterized by a high density of newly formed blood vessels, immunosuppressive cells and inhibitory cytokines. These factors work together to shield tumor cells and hinder the infiltration of CAR-T cells (233). Local drug delivery is considered as one of the most effective measures to tackle this issue, and it can be accomplished by directly administering drugs into the tumor site in various tumor models. Local delivery via intracranial/intravenous drug administration has yielded positive results in models of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, glioblastoma and colorectal cancer with liver metastases (234,235). Moreover, an alternative method for delivering CAR-T cells into solid tumors involves the use of implantable biopolymer devices. This approach eliminates the need for direct injection into the tumor, allowing for prolonged exposure of tumor cells to high concentrations of immune cells. In mouse models with normal immune function but afflicted with pancreatic cancer and melanoma, the use of a bioactive vector substantially enhanced T cell expansion and function (40).

Runt-related transcription factor 3 (Runx3) protein has been found to promote T cell re-accumulation in tumor tissue. In melanoma mouse models, the expression of the Runx3 gene has been found to effectively promote the accumulation of T cells in tumor tissues and suppress tumor growth (236). In addition, accumulation of collagen and heparan sulfate proteoglycans in tumor tissue hampers the penetration of T cells into the extracellular matrix, but this obstacle can be overcome by overexpressing heparanase. Heparanase, an enzyme naturally present in T cells but absent in CAR-T cells, degrades heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Research conducted by Caruana et al (237) confirmed that CAR-T cells engineered to produce heparanase could essentially reduce tumor volume. In solid tumors, chemokines secreted by the tumor can hinder the penetration and migration of T cells. However, certain chemokine receptors expressed on T cells can recognize these chemokines present in the TME. Therefore, it is possible to enhance the homing and infiltration of CAR-T cells by engineering them to express these specific chemokine receptors. This approach has shown promise in increasing the significance of CAR-T cell therapy (238).

Promoting the persistence of CAR-T cells

A major factor contributing to the inefficacy of CAR-T cell therapy is the notable decline in the persistence of CAR-T cells. This decline is primarily a result of the immune system's impaired ability to identify foreign peptides derived from CAR, which subsequently leads to modifications in T lymphocytes through immune-mediated mechanisms (239,240). Methods to improve the persistence of CAR-T cells mainly include binding to oncolytic viruses and engineering chimeric inverted receptors. Xia et al (41) suggested that combining oncolytic viruses with CAR-T cells improved the activity of CAR-T cells. In addition, it was suggested that being infected with oncolytic viruses could potentially boost the capacity of CAR-T cells to infiltrate tumors, overcome immune system suppression and ultimately enhance their ability to persist (241-243). In addition, engineered chimeric inversion receptors represent a practical way to improve the persistence of CAR-T cells by transforming the immunosuppressive surroundings into an immune-stimulating environment. IL-4 secreted by the tumor exerts an inhibitory impact on T lymphocytes. A novel approach called reverse CAR has been engineered on T lymphocytes, where it incorporates the extracellular domain of IL-4 and the intracellular domain of IL-7. Mohammed et al (105) reported that reverse CAR had the ability to transform the inhibitory signal of T lymphocytes into a stimulatory signal, thereby enhancing the persistence of CAR-T cells. Liu et al (244) engineered a chimeric PD-1 receptor by combining a truncated PD-1 extracellular domain with the transmembrane and internal domains of CD28, transforming the PD-1's inhibitory signal into a stimulating signal to improve the persistence of CAR-T cells. Furthermore, secretion of cytokines by CAR-T cells, such as IL-2, IL-15 and IL-18, has been demonstrated to selectively amplify memory CAR-T cells and enhance their persistence (245). Feucht et al (197) reported that modulating the ITAM of CD247 could enhance CAR signaling, leading to a reduction in T cell exhaustion. Continuous activation signal generated by spontaneous clustering of CAR molecules during in vitro expansion of CAR-T cells resulted in T cell exhaustion, which hampered the therapeutic effectiveness and the persistence of CAR-T cells in vivo. Thus, it would be beneficial to regulate the density of CAR molecules on the cell surface to prevent the aggregation of CARs and subsequent sustained cell activation (246).

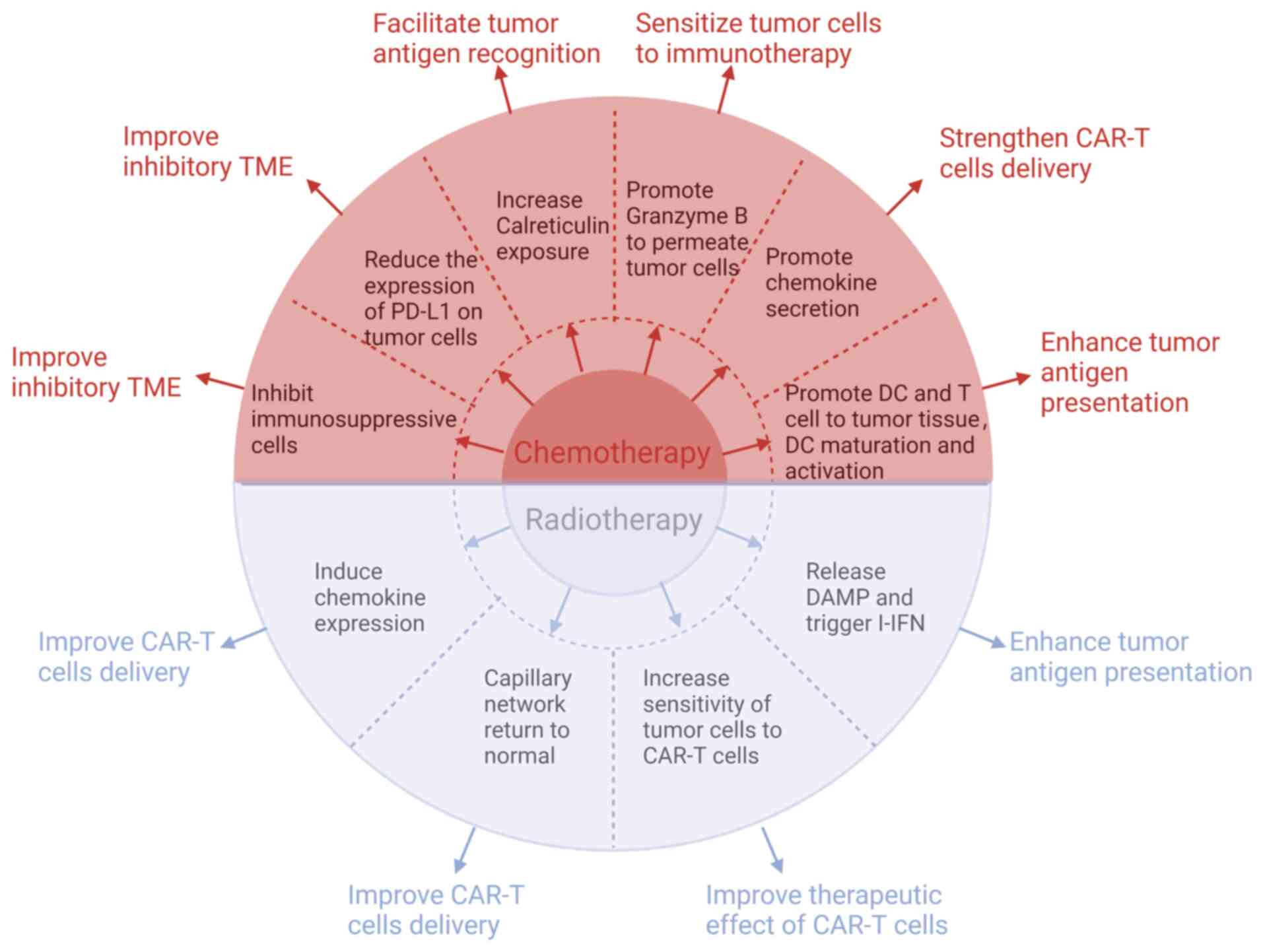

6. Combined application of CAR-T cells with chemotherapy or radiotherapy

CAR-T cell therapy for OS continues to face several obstacles. Thus, researchers have made several efforts to boost the effectiveness of CAR-T cell therapy in OS by exploring potential approaches such as integrating it with radiotherapy or chemotherapy (Fig. 6) (18).

Combined application of CAR-T cells with chemotherapy

The efficacy of local control of CAR-T cells or chemotherapy alone in the treatment of high-grade OS remains suboptimal (247). As a result, certain researchers have proposed that CAR-T cells applied together with chemotherapy could potentially enhance the treatment outcome.

Chemotherapy improves inhibitory TME

Chemotherapeutic agents such as adriamycin, methotrexate, cisplatin and ifosfamide, possess not only tumor-reducing properties but also notable immunomodulatory effects (43). Regular administration of low-dose cyclophosphamide can effectively decrease the quantity and suppressive function of Tregs. Furthermore, it has been observed to augment the presence of CD8+ T cells, which have a pivotal function in triggering immune responses against malignant tumors (248,249). Adriamycin, when combined with CAR-T cells, boosts their antitumor efficacy by suppressing Tregs and MDSCs, leading to a significant inhibition of tumor growth in both mice and humans (250,251). In the context of solid tumors, Seliger and Quandt (252) noted that tumor cells possessed the capability to enhance the levels of immune checkpoint molecules, namely PD-L1 and PD-L2. This mechanism effectively hindered the activity of T and CAR-T cells attempting to penetrate and combat the tumor. Chulanetra et al (43) observed that adriamycin was able to increase the response of OS to GD2-CAR-T cells. This effect was achieved by diminishing the expression of PD-L1, an immune checkpoint, in OS cells. In murine models of pancreatic and prostate cancer, a pretreatment strategy involving cyclophosphamide followed by administration of CAR-T cells led to a significant change in the TME. It effectively shifted the TME from an anti-inflammatory state to a proinflammatory state, thereby stimulating the production of chemokines. These chemokines play a crucial role in attracting CAR-T cells and ultimately revitalize immunologically 'cold' tumors, transforming them into 'hot' tumors that are highly responsive to treatment (253).

Chemotherapy enhances T-cell trafficking to the tumor

Overcoming the obstacle of efficiently transporting T cells to the tumor site remains a critical concern in enhancing the potency of CAR-T cell treatment. Research on mice at preclinical stage indicated that there was a link between limited migration of T cells and diminished levels of chemokine expression (254). CXCL9 and CXCL10 induced by adriamycin could attract NKG2D-CD8+ T cells to OS cells and promote NKG2D-CD8+ T cell homing (250). The study by Srivastava et al (255) revealed that, when mice were pre-treated with oxaliplatin and cyclophosphamide, a notable alteration in the TME was observed. The occurrence triggered an inflammatory reaction, leading to an increased release of CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL16 by tumor macrophages. This facilitated ROR1-CAR-T cells to enter and effectively target lung tumor cells, leading to a significant improvement in their ability to eliminate them (255). The study by Srivastava et al (255) was not on OS but on lung tumors. However, both lung tumors and OS are solid tumors and both have a similar TME. Hence, further exploration into the combination of chemotherapy and CAR T-cell therapy for enhancing the therapeutic outcomes of OS is a valuable endeavor.

Chemotherapy increases tumor cell sensitivity to immunotherapy

Following targeted chemotherapy, there was a notable increase in the presence of mannose-6-phosphate receptor on cancer cells, which, in turn, allowed granzyme B to enter these cells more effectively. This process not only aided in self-regulation but also heightened the responsiveness of tumor cells to immunotherapy through autophagy (256-258). Parente-Pereira et al (259) conducted a preclinical investigation revealing that combining HER2-CAR-T cells with a low dose of carboplatin not only amplified the sensitivity of tumor cells to HER2-CAR-T cell-induced cytotoxicity but also augmented the overall effectiveness of antitumor treatment. While the mechanism behind increased tumor tissue susceptibility to immunotherapy after chemotherapy remains unclear, Proietti et al (260) have observed improved efficacy in tumor treatment when combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy. Therefore, it could be hypothesized that chemotherapy may improve the ability of CAR T-cell therapy in the treatment of OS and may be a promising direction for future insightful research.

Chemotherapy can enhance tumor antigen recognition and presentation

According to Senovilla et al (261), exposure of calreticulin can be increased by certain chemicals, such as paclitaxel and vinblastine, which leads to enhanced recognition of tumor cells. Additionally, chemotherapeutic agents have the ability to enhance the presentation of tumor antigens. The primary pathways involved are as follows: Firstly, activation of autophagy by certain chemotherapeutic drugs results in the release of ATP in tumor cells. This crucial step subsequently encourages the infiltration of dendritic cells and T lymphocytes into tumors, thus facilitating the presentation of tumor antigens (262). Secondly, chemotherapeutic agents can stimulate dying cancer cells to release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as high mobility group box 1 (HMGB 1), which could then be recognized by Toll-like receptor 4. This recognition promotes the activation of dendritic cells, leading to a significant increase in the body's ability to fight against tumor cells using T cells (263). Thirdly, chemotherapy prompts tumor or stromal cells to generate type I IFN, which activates dendritic cells, initiating cross priming of T cells and effectively controlling the tumor (264,265). Based on the aforementioned studies, it can be proposed that chemotherapy can increase the antigen presentation of OS cells, which can be more easily recognized and killed by CAR-T cells.

Combined application of CAR-T cells with radiotherapy

Radiotherapy can improve the therapeutic effect of CAR-T cells

Radiotherapy has the dual benefit of not only eliminating tumor cells, but also triggering a targeted immune response against the tumor, offering a potential treatment for both local and distant metastatic tumors (266). DeSelm et al (42) found that administering low-dose total body irradiation can enhance pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells' responsiveness to CAR-T cells, enabling the elimination of tumor cells with a reduced dose of CAR-T cells, consequently reducing CRS incidence and enhancing treatment effectiveness. Thus, it is plausible to consider that radiotherapy may enhance the effect of CAR-T cells in the treatment of OS.

Radiotherapy can enhance tumor antigen presentation

Research conducted by Walle et al (267) highlights how radiotherapy has the ability to amplify tumor antigen presentation, thereby offering a promising avenue for improving cancer therapy. The study conducted by Apetoh et al (268) shed light on the ability of radiotherapy to stimulate apoptosis and necrosis within tumor cells, consequently causing the release of DAMPs. Among these patterns, HMGB 1 was particularly observed. Subsequently, the presence of DAMPs and tumor antigens within the TME can activate type I IFN, thereby initiating a series of innate and adaptive immune responses against tumor cells (269,270). Previous studies have reported that the interplay between innate and adaptive immune responses promotes maturation and activation of dendritic cells to increase tumor antigen presentation (271,272). Thus, radiotherapy may enhance OS tumor antigen presentation, making it more readily recognized and inhibited by CAR-T cells.

Radiotherapy can enhance CAR-T cell infiltration

Effective infiltration of CAR-T cells into the tumor are critical steps in inhibiting OS. Weiss et al (273) demonstrated that the concurrent use of local radiotherapy and NKG2D-CAR-T cells enhanced the trafficking of CAR-T cells to the tumor site, leading to an augmented antitumor response of T cells in glioblastoma. Moreover, previous studies have reported that local radiotherapy can stimulate the production of chemokines such as CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL16, which in turn increases the recruitment of T cells into the TME, thereby facilitating tumor-suppressive effects (274,275). In addition, low-dose radiotherapy promoted the secretion of IFN-γ, leading to the normalization of the capillary network, which promoted the infiltration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes into the tumor (276). As a result, radiotherapy appears to have the potential to enhance the trafficking of CAR-T cells to OS, leading to improved treatment outcomes for overall survival.

CAR-T cell therapy plus chemoradiotherapy

Given the crucial role of chemoradiotherapy in treating OS, it represents a novel and innovative approach to amplify the antitumor impact of CAR-T cell therapy through this method. However, CAR-T cell therapy combined with chemoradiotherapy for treating OS still faces numerous problems. Firstly, chemoradiotherapy results in treatment-related toxicities, including effects on the immune system of the host such as lymphopenia (277). Additionally, the utilization of CAR-T cells for the treatment of OS is at an early stage, and the exploration of combining chemoradiotherapy with CAR-T cell therapy for OS requires further investigation. While the mechanism of CAR-T cells in conjunction with chemoradiotherapy for treating OS is not yet fully understood, this approach remains a promising treatment option. In summary, CAR-T cell therapy combined with chemoradiotherapy presents a new and innovative approach to treat OS. However, additional research is required to improve understanding of its clinical efficacy and mechanisms of action.

7. Conclusions

CAR-T cell immunotherapy represents a new alternative strategy for the treatment of OS. A variety of target antigens, including DNAJB8, HER2, CD276, CD166, EphA2, GD2, IL-11Rα, IGF-1R, ROR1, NKG2D, CSPG4 and CD44v6, have been explored for CAR-T cell establishment and OS cell elimination, and have produced encouraging results. However, CAR-T cell therapy in OS still encounters several challenges, including the absence of specific tumor antigens, tumor antigen evasion, inhibitory TME, off-target effects and CRS. Consequently, numerous measures have been undertaken to enhance the effectiveness of CAR-T cells, which encompass structural modifications of CAR-T cells, TME enhancement, improved persistence and homing capabilities, engineering CAR-T cells to target the OS vasculature, and combining CAR-T cells with radiotherapy, chemotherapy or checkpoint inhibitors. In conclusion, CAR-T cell therapy represents a novel method for the treatment of OS, offering an alternative therapeutic option for patients with OS.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

TY, YW and YZ wrote parts of the initial draft of this review. WJ modified the initial draft of the manuscript. JJ contributed to the figures. WJ and MW edited the initial draft of this paper and made final changes to the final version before submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Miss Ran Meng (student; Chengde Medical University) and Miss Zhijia Ma (postgraduate; Tianjin Medical University) for identifying relevant literature in the manuscript and for editing the manuscript.

Funding